blog counter

By Robert K. Arakaki

By Robert K. ArakakiA Journey to Orthodoxy

It was my first week at seminary. Walking down the hallway of the main dorm, I saw an icon of Christ on a student’s door. I thought:

“An icon in an evangelical seminary?! What’s going on here?”Even more amazing was the fact that Jim’s background was the Assemblies of God, a Pentecostal denomination. When I left Hawaii in 1990 to study at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, I went with the purpose of preparing to become an evangelical seminary professor in a liberal United Church of Christ seminary. The UCC is one of the most liberal denominations, and I wanted to help bring the denomination back to its biblical roots. The last thing I expected was that I would become Orthodox.

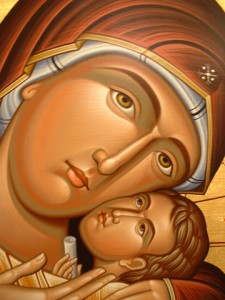

Called by an Icon

After my first semester, I flew back to Hawaii for the winter break. While there, I was invited to a Bible study at Ss. Constantine and Helen Greek Orthodox Church. At the Bible study I kept looking across the table to the icons that were for sale. My eyes kept going back to this one particular icon of Christ holding the Bible in His hand. For the next several days I could not get that icon out of my mind.

I went back and bought the icon. When I bought it, I wasn’t thinking of becoming Orthodox. I bought it because I thought it was cool, and as a little gesture of rebellion against the heavily Reformed stance at Gordon-Conwell. However, I also felt a spiritual power in the icon that made me more aware of Christ’s presence in my life.

In my third year at seminary, I wrote a paper entitled, “The Icon and Evangelical Spirituality.” In the paper I explored how the visual beauty of icons could enrich evangelical spirituality, which is often quite intellectual and austere. As I did my research, I knew that it was important that I understand the icon from the Orthodox standpoint and not impose a Protestant bias on my subject. Although I remained a Protestant evangelical after I had finished the paper, I now began to comprehend the Orthodox sacramental understanding of reality.

After I graduated from seminary, I went to Berkeley and began doctoral studies in comparative religion. While there, I attended Ss. Kyril and Methodios Bulgarian Orthodox Church, a small parish made up mostly of American converts. It was there that I saw Orthodoxy in action. I was deeply touched by the sight of fathers carrying their babies in their arms to take Holy Communion and fathers holding their children up so they could kiss the icons.

The Biblical Basis for Icons

After several years in Berkeley, I found myself back in Hawaii. Although I was quite interested in Orthodoxy, I also had some major reservations. One was the question: Is there a biblical basis for icons? And doesn’t the Orthodox practice of venerating icons violate the Ten Commandments, which forbid the worship of graven images? The other issue was John Calvin’s opposition to icons. I considered myself to be a Calvinist, and I had a very high regard for Calvin as a theologian and a Bible scholar. I tackled these two problems in the typical fashion of a graduate student: I wrote research papers.

In my research I found that there is indeed a biblical basis for icons. In the Book of Exodus, we find God giving Moses the Ten Commandments, which contain the prohibition against graven images (Exodus 20:4). In that same book, we also find God instructing Moses on the construction of the Tabernacle, including placing the golden cherubim over the Ark of the Covenant (Exodus 25:17–22). Furthermore, we find God instructing Moses to make images of the cherubim on the outer curtains of the Tabernacle and on the inner curtain leading into the Holy of Holies (Exodus 26:1, 31–33).

I found similar biblical precedents for icons in Solomon’s Temple. Images of the cherubim were worked into the Holy of Holies, carved on the two doors leading into the Holy of Holies, as well as on the outer walls around Solomon’s Temple (2 Chronicles 3:14; 1 Kings 6:29, 30, 31–35). What we see here stands in sharp contrast to the stark austerity of many Protestant churches today. Where many Protestant churches have four bare walls, the Old Testament place of worship was full of lavish visual details.

Toward the end of the Book of Ezekiel is a long, elaborate description of the new Temple. Like the Tabernacle of Moses and Solomon’s Temple, the new Temple has wall carvings of cherubim (Ezekiel 41:15–26). More specifically, the carvings of the cherubim had either human faces or the faces of lions. The description of human faces on the temple walls bears a striking resemblance to the icons in Orthodox churches today.

Recent archaeological excavations uncovered a first-century Jewish synagogue with pictures of biblical scenes on its walls. This means that when Jesus and His disciples attended the synagogue on the Sabbath, they did not see four bare walls, but visual reminders of biblical truths.

I was also struck by the fact that the concept of the image of God is crucial for theology. It is important to the Creation account and critical in understanding human nature (Genesis 1:27). This concept is also critical for the understanding of salvation. God saves us by the restoration of His image within us (Romans 8:29; 1 Corinthians 15:49). These are just a few mentions of the image of God in the Bible. All this led me to the conclusion that there is indeed a biblical basis for icons!

What About Calvin?

But what about John Calvin? I had the greatest respect for Calvin, who is highly regarded among Protestants for his Bible commentaries and is one of the foundational theologians of the Protestant Reformation. I couldn’t lightly dismiss Calvin’s iconoclasm. I needed good reasons, biblical and theological, for rejecting Calvin’s opposition to icons.

My research yielded several surprises. One was the astonishing discovery that nowhere in his Institutes did Calvin deal with verses that describe the use of images in the Old Testament Tabernacle and the new Temple. This is a very significant omission.

Another significant weakness is Calvin’s understanding of church history. Calvin assumed that for the first five hundred years of Christianity, the churches were devoid of images, and that it was only with the decline of doctrinal purity that images began to appear in churches. However, Calvin ignored Eusebius’s History of the Church, written in the fourth century, which mentions colored portraits of Christ and the Apostles (7:18). This, despite the fact that Calvin knew of and even cited Eusebius in his Institutes!

Another weakness is the fact that Calvin nowhere countered the classic theological defense put forward by John of Damascus: The biblical injunction against images was based on the fact that God the Father cannot be depicted in visual form. However, because God the Son took on human nature in His Incarnation, it is possible to depict the Son in icons.

I was surprised to find that Calvin’s arguments were nowhere as strong as I had thought. Calvin did not take into account all the biblical evidence, he got his church history wrong, and he failed to respond to the classical theological defense. In other words, Calvin’s iconoclasm was flawed on biblical, theological, and historical grounds.

In my journey to Orthodoxy, there were other issues I needed to address, but the issue of the icon was the tip of the iceberg. I focused on the icon because I thought that it was the most vulnerable point of Orthodoxy. To my surprise, it was much stronger than I had ever anticipated. My questions about icons were like the Titanic hitting the iceberg. What looked like a tiny piece of ice was much bigger under the surface and quite capable of sinking the big ship. In time my Protestant theology fell apart and I became convinced that the Orthodox Church was right when it claimed to have the fullness of the Faith.

I was received into the Orthodox Church on the Sunday of Orthodoxy in 1999. On this Sunday the Orthodox Church celebrates the restoration of the icons and the defeat of the iconoclasts at the Seventh Ecumenical Council in AD 787. On this day, the faithful proclaim,

“This is the faith that has established the universe.”It certainly established the faith of this Calvinist, as the result of the powerful witness of one small icon!

Read more: How an Icon Brought a Calvinist to Orthodoxy : Journey To Orthodoxy

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου